Reviews (863)

Klute (1971)

Klute is a breathtaking and uniquely original film – that is, if the viewer gives it a chance and, ideally, approaches it without any expectations or foreknowledge. That may not be easy, given the film’s misleading title. John Klute is not the main character, but rather only a key catalyst of events. On the other hand, the title helps to point out that the film is connected with the noir genre and, in the spirit of other movies of the time, such as The Long Goodbye and Night Moves, does not fulfil the criteria of that genre in its classic form, but rather subversively deconstructs it and transforms it into something extraordinary. Despite the original screenplay (which in the traditional spirit was about a small-town cop who gets mixed up with criminals in New York), the film focuses not on the detective, but rather on the femme fatale, who is not dealt with as an object, but rather as a complex and complicated character. Pakula acknowledges that Klute thus violates the Hitchcockian rule of genre films by focusing on psychology instead of attractions (Klute inadvertently sets forth the difference between the true sophistication of the character and the bluffing superficial psychologisation of characters in modern sophisticated genre movies and blockbusters). Bree Daniels, played by Jane Fonda, thus becomes the central character and through genre elements the film is immersed in the issues of sex as a power play and seduction as acting based on control over others and over the situation, but it mainly becomes a portrait of this woman. The actress, for whom, after the phenomenal They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, this was the second role illustrating her personal growth into a mature, emancipated woman, contributed significantly to the final form of the film. At her request, she not only spent time with real call girls, took a large part of the costumes from her own wardrobe and even lived on the set of the protagonist’s apartment for several days before shooting began, but she also took an improvisational approach to a number of scenes in order to fully get into them. So, why isn’t the film called Daniels? Because for the confident yet self-doubting woman, the detective is a mirror of the contrast of both her outward image and her inner self, her control and helplessness, or simply her ambiguity, which she herself tries to cope with. Despite its title, Klute is not only a milestone in American cinema from the perspective of female protagonists, but a departure from traditional genre formulas and rules, which is represented by the emancipatory, ground-breaking nature of the film’s female character and the verbalisation of her perspective. Alan J. Pakula always highlighted Jane Fonda’s merits as well as contribution that other members of the creative team made to the final form of the film. Klute is thus a representation of the ideal of a film as a collective work, where the director does not bend the will of other members of the crew to his vision, but is rather guided by the inspiration and talent of others. Cinematographer Gordon Willis made an incredible contribution to the film with his incredibly sophisticated fragmented compositions, dramaturgically motivated camera approaches and expressively gloomy lighting, and composer Michael Small created disturbing, paranoid music mixed with the commotion of the scenes. In addition to the contrapuntal editing and the costumes with a feel for the authenticity of New York and presentation of the characters, Donald Sutherland, with his restrained performance, helped to shape the titular protagonist into the role he was supposed to have in this story. Narratively and stylistically, Klute goes beyond the boundaries of noir alternately into the realms of thriller and romance, offering an absorbing, chilling and unique viewing experience (the scene involving shopping for fruit is breathtaking due to its intimacy and fragility in showing love, while again displaying the astonishing interplay of all of the above-mentioned creative forces).

Gone Girl (2014)

Like Paul Thomas Anderson, David Fincher is moving toward an increasingly subdued and austere form of perfection in his directing. After the first part of their respective filmographies, which was characterised by ostentatious formal bombast culminating, in Fincher’s case, in Panic Room with abundant playing with flying camerawork in flawless reality-defying approaches, greater efficiency and modesty are increasingly becoming hallmarks of their later films. That doesn’t mean that Fincher and Anderson have become some sort of ascetics, but only that their mastery is reflected in the fact that they do not in any way attract attention to themselves. We could almost mention the return of studio style, where the form also served to maximally draw viewers into the story and did not have to draw attention to itself, except this time it’s not a matter of following certain conventional rules, but expressing flawless familiarisation with the craft and maximally well-though-out composition of every shot so that it serves the work as a whole. Gone Girl is Fincher’s riveting masterclass on outwitting viewers, where at the same time we are astonished not only by the narrative (typically about characters who deceive those around them and inventively work with their own image), but also by how seemingly easily and subtly the film guides us and keeps us chained to the screen and holding our breath throughout its runtime.

The SpongeBob Movie: Sponge on the Run (2020)

With a truly heavy heart, I have to say that despite its tremendous promise, the third feature-length SpongeBob movie is a big disappointment. As in the case of its immediate predecessor, the main problem with Sponge on the Run consists in the fact that the producers evidently did not trust the core screenwriters of the series. The hiring of Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger, who have the massive hits Kung Fu Panda and Trolls under their belts, reeks of an attempt to place a safe bet, but it actually trips up the film. Aibel and Berger have the preceding Sponge Out of Water on their conscience, and this time it is even more obvious that this duo may be able to make a popular animated feature that does not offend anyone and makes a lot of money, but they definitely do not understand the essence and qualities of SpongeBob (or rather they don’t have those qualities themselves). Though the series about the yellow sponge abounds with brilliantly expressive animation, Dadaist absurdity and meta humour, that does not distinguish it in principle from other series from the end of the 1990s shown on Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network. Rather, its uniqueness consisted in the characterisation of SpongeBob and the series’ overall style deriving from that characterisation, into which Stephen Hillenburg projected his famous good-heartedness, which radiated from every episode. Aibel and Berger, on the other hand, are just calculating cynics who have built their success on strictly filling in tried and true templates and on stupid literalism. Under their leadership, therefore, SpongeBob and his friends have to talk about kindness and empathy in forced sentimental scenes instead of just being themselves. In their script, SpongeBob lost his classic attributes, particularly exaggeration and exuberance, as well his natural sincerity and resourcefulness. The film is basically saved and elevated by its top-quality visual element, which is breathtaking in its innovative grasp of artistic and animation stylisation of 3D characters and objects. Furthermore, it preserves the expressiveness of cartoon animation and has fascinating plasticity and textures. However, the tremendous hard work of the animators has nothing to properly lean on. The hopelessness of the screenplay becomes evident especially in the cameo roles, which again lack exaggeration and are stretched beyond the limits of their wow effect, thus becoming the hollow and unimaginative opposite of what worked in the very first SpongeBob film. The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie not only does not age, but thanks to the involvement of Hillenburg and leading talents from the series, it remains an impressive and, at the same time, moving and infinitely entertaining example of what a real SpongeBob feature should look like, unlike this mediocre movie in which SpongeBob is merely present.

Transformers: The Last Knight (2017)

Under Michael Bay’s direction, Transformers has gradually crystallised into a supremely atypical contribution to the current line of franchise blockbusters. All of the other films based on comic books or toys take heed to offer adult fans a spectacle that, though childish at its core, is supposed to give the impression of being grown-up and serious in its overall execution (from the screenplays and casting to the style of promotion). Conversely, Bay serves up the exact opposite – ultra-unserious, openly irreverent and ridiculously overblown spectacles packed with affectation and kitsch. Even though this is indeed largely due to his bombastic, egomaniacal and macho nature, this is not some sort of desecration of the original franchise’s original form, but rather a faithful return to its roots and a reminder of what those who were weaned on the original series no longer want to admit. While the comic-book producers are rewriting history with new reboots that erase all of the inadequate aspects of the earlier incarnations, Bay’s Transformers seems to make a point of accentuating all of the haphazardness, degeneracy and problematic aspects of the 1980s that the nerds have already blissfully erased from their memory. But that’s actually how Transformers used to be. Only the question remains of whether Bay’s grasp of the franchise, which accentuates all of those residual ills, represents continuity with conscious subversiveness or whether Bay simply and fundamentally personifies them by coincidence. ____ There has been much discussion about how unfortunate acting icons and prominent character actors, like Sir Anthony Hopkins in this case, are forced to demean themselves (in return for a generous payday) in Transformers movies by cartoonishly making faces and delivering absurd monologues. That fits beautifully into the image of Bay as a desecrator of all values, but again, we can also see this as part of the franchise’s heritage. Eric Idle, Leonard Nimoy and Orson Welles took turns at the microphone for the first animated feature, while giant robots danced to Weird Al Yankovic’s “Dare to Be Stupid” and the movie’s most epic moment was underscored by Stan Bush’s cheesy rocker “The Touch”. ___ Bay can be seen as both a mainstream John Waters and a Hollywood version of Czech trashmaker Zdeněk Troška – a perverted admirer of conventional vulgarity and consumerist gluttony, but also a self-proclaimed promoter of traditional values. As in Troška’s case, in Bay’s works the authorities and scientists take the form of hysterically incompetent jacks-in-the-box, while the arrogant earthy heroes seemingly save everything, but are also portrayed as equally ridiculous, aggressive and sociopathic characters who treat each other with disdain. We associate Bay’s films with rampant ridiculousness, but are executed with an almost obsessive degree of craftsmanship. It’s thus all the more surprising that the coarseness and vulgarity of the preceding films is not present this time, at least not in such an obvious form. This surely has something to do with the fact that, for the first time, the screenwriting has caught up with, or even surpassed, Bay himself. From one instalment to the next, the series goes more against the grain and becomes gaudier and more absurd. Previously, it was enough for Bay to employ his own whims – whether shots of the Transformer’s testicles, the appendage reaching around the car and hitting a soldier in the face, or the malevolent objectification of Megan Fox in the first film, which successfully degrades the only positively depicted and active character in the whole series simply by how she’s captured on camera and how the other characters react to her. This time, however, the screenplay finally cast off the shackles and comes up with a phantasmagorical alternate history of the Transformers that is so wonderfully boorish that not even Bay can vulgarise it any further. Thanks to the screenplay, the film breaks away from the run-of-the-mill globetrotting nature of blockbusters, where photogenic exotic locations are supposed to bring the desired wow factor to the action. Instead of moving through space, it goes against the flow of time and, what’s more, does so without the shackles of reality and causality. Whereas Avengers: Endgame used this technique to express sentimental reverence, Transformers sets out like Monty Python to disparage (Stanley Tucci as the overwrought Merlin is extremely reminiscent of John Cleese’s acting performances). Paradoxically – judging by the reactions – viewers are willing to celebrate Tarantino’s playing around with historical figures and periods and to have fun with alternate histories like Iron Sky and even Wonder Woman, but for some reason they unreasonably demand realism and seriousness from Bay and his movies about giant robots financed by a toy company. ___ Under Bay’s direction, the ultimate perverse power of the blockbuster emerges in a work that devours itself to the point of being execrable. Except that Bay’s fifth Transformers is no mushy turd, but rather a turd with flawless structure, density and shape. Yes, it’s overblown, bombastic, megalomaniacal and silly, but thanks to that and the extent of those essential qualities, it is also perfect and beautiful. As it explosively blasts through the boundaries of corporate product, the fifth Transformers is the most unrestrained and, at its core, the most original blockbuster of the new millennium. Though there is some truth in the notion that Michael Bay has only been making variations of the same model throughout his career, we see in the level of craftsmanship of the scenes here that he is still stratifying his experiences while outdoing himself with new challenges. Much has been said and written about Bay’s editing and camera compositions, but little is made of the fact that, despite the tremendous amount of CGI, he creates the bulk of the action on set, thanks to which his action scenes have such an amazing physical dimension and tremendous wow effect. ___ Michael Bay is actually the anti-Nolan. While the creator of Inception and Tenet offers viewers intellectual blockbusters in which the spectacle is both sensual and cerebral, Bay delivers an overwhelming, bombastic overload of polished and ambitiously executed stupidity, shallowness, kitsch and pathos. The fifth Transformers completely bypasses the viewers’ rationality and values and aims straight for the depths of the unconscious to absolutely satisfy their needs with maximum degeneracy and gluttony. Bay serves us pure blockbuster bacchanalia.

Lake Michigan Monster (2018)

Lake Michigan Monster proves that a pastiche can be both eclectic and original, as well as infectiously entertaining. Hyperactive filmmaker Ryland Brickson Cole Tews combines the visual style of Guy Madin (whom he thanks in the closing credits) with the inventive originality of Karl Zeman, the disarming naïveté of classic monster flicks and the phantasmagorical playfulness and Dadaist exuberance of SpongeBob. We could go on and on with allusions and inspirational references, but the key point remains that this enthusiast project put together by a group of friends, who take turns in front of and behind the camera, enchantingly combines the fantastical with the commonplace and the imaginative with cheapness, not only in terms of the behind-the-scenes creative work, but also in the narrative style and the story itself. The story is absurdly simple, but in this case the path from the beginning to the end peculiarly does not follow a straight line. Like a crazy doodle, it takes absurd turns that don’t necessarily push the narrative forward in any way (on the contrary, it sometimes brings the narrative to a halt or even takes it backwards), because the playful imaginativeness here takes priority over ordinary logic. For some, this magnificent “nautical nonsense” will be an annoying display of affectation and zero-budget shoddiness, but for others, it is a longed-for nutty amusement that blends bizarreness with naïveté and terror in a sort of intoxicatingly short-circuited anti-logic. In fact, the most adequate comparison with which to describe Lake Michigan Monster is as a cross between SpongeBob and Forbidden Zone – it never occurred to me that these seemingly completely opposite poles of phantasmagoria could be so naturally combined, but it just goes to show that there really are no limits to imagination.

Boy and Bicycle (1965) (amateur movie)

Ridley Scott’s short-film debut is a remarkable cross between the aesthetics of British kitchen-sink realism and the expressive advertising style of hyper-aestheticised tableaux, the first generation of which Scott himself subsequently became one of the most distinctive experts. But like his brother Tony’s short One of the Missing, which followed a year later, Boy and Bicycle remains a formal exercise that in retrospect offers a look at the roots of the director's subsequently fully formed style and approach to his craft.

Society (1989)

QAnon the Movie, or how an unhinged high-school jock finds out that there is something very twisted at the core of California’s elite society. In its day, Society must have been a great revelation for unsuspecting viewers who rented it on VHS. But they probably had a pretty good idea of what was in store for them even then, as Brian Yuzna had clearly created a category of his own thanks to his association with Re-Animator. Therefore, the paranoid storyline that the film tries to build up through most of its runtime doesn’t work very well, since everyone guesses that the protagonist isn’t merely hallucinating. Unfortunately, this storyline takes up the greater part of the film and the messy Dali-esque surreal satire comes along only near the end. After all, the whole project exhibits the classic ills of VHS trash flicks, where the central goofy idea doesn’t merit more than a medium-length project (or rather, it isn’t developed into a proper screenplay that can fully exploit it), but empty scenes stretch it out to a feature-length runtime. But what we will say is that nobody is going to watch this movie for its screenplay (which really doesn’t work and actually goes from nowhere to nowhere), but only for the creations of special-effects master Screaming Mad George, which are excellent and grotesquely disturbing. Society is thus an exemplary illustration of the rule that the prevailing impression that a film makes is based on the viewing experience from the last quarter of the film.

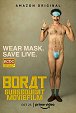

Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2020)

The second Borat is an overblown PR bubble as well as a movie that was hastily slapped together in an effort to coast on the moods of pre-election America. As Sacha Baron Cohen himself admits, he could not go back to the same well a second time simply because people already knew the Borat character. Therefore, the second film is built to a far lesser extent on confrontations with unsuspecting people who reveal themselves vis-à-vis the caricature. It rather relies mainly on a screenplay with a traditional narrative structure and the clichéd dramatic arc of the main characters, which only becomes overwrought through repetitive jokes. Paradoxically, the second Borat gives the impression of being a rapidly fermenting copy of Cohen’s chilling masterclass in Who Is America?. Though he again wagers on ratcheting up the awkwardness, in most situations, unfortunately, confrontational provocation remains only wishful thinking. It is obvious that Cohen has to try really hard to draw something usable out of the situations, but that does not prevent the PR department from spinning a carousel of spectacular claims (the apex of futility is the attempt at fomenting a scandal with Giuliani). The Borat character and the attempt to bring unnecessary dramatic consistency to the film repeatedly prove to be its main hindrances. Cohen’s need to maintain a trace of the Kazakh dolt in his new prankish alter egos by means of an accent undermines a number of scenes by limiting the potential for provocation. If Borat’s first look into American culture brought forth a lot of frightening and disturbing revelations about the American character, the return of the self-proclaimed reporter shows only a country in a state of lethargy, where even the greatest provocation will be met only with silence and raised eyebrows. The clown lost his power derived from placing a mirror in front of the country, because during his absence, America itself chose a much grimmer clown as its president and the essence within America, once previously revealed with shame, was transformed from the grotesque dark side into the norm of social discourse. It is also appropriate to note that infotainment also underwent a change during that time and that confrontation leading to throwing off façades is now a common or rather frequently updated part of journalistic comedy programmes such as The Daily Show and The Opposition with Jordan Klepper. However, that does not mean Cohen’s style of ultra-awkward confrontations has lost its effectiveness, as was confirmed by the outstanding Who Is America? project. Borat itself, or rather the transformation of its purpose, is what stands in the way. The first film occupied the plane of confrontational malice with carefully selected targets. The second film becomes a desperate slave of the narrative line, which has the consequence of preserving the dysfunctional and obviously unsuccessful pranks (the entire sequence with a fax machine, the uber driver, etc.), which previously would have wound up on the cutting-room floor or the film’s creators would have tried to stage again with other victims, if they hadn’t had a release deadline before the American elections. Cohen’s activistic agitation paradoxically drags the film to the bottom. It also brings into it an element of unnaturalness and staging, which is manifested in the well-meaning sequences of the touching humanisation of Borat and his daughter (babysitter and synagogue). The general proclamation that Borat’s return offers necessary relief for these times, thus (in addition to accepting pre-formulated claims) rather reflects an even more desperate state of the culture and society than Borat can uncover. There are flashes of that in the film and something could happen, but that would require completely reworking the concept and, mainly, rejection of the predetermined storyline. We thus go back to the beginning for confirmation that, unlike Cohen’s aforementioned series project, this film is not about America, but only about Borat, who has gone from being a functional catalyst to a dysfunctional character.

Seven Layer Dip (2010)

At first glance, Seven Layer Dip is an average short with fine choreography, but as mentioned in the closing credits, it was created entirely by the stunt duo of Monique Ganderton and Sam Hargrave. And not only the performances in front of the camera, but also behind it. Thus, when one of them is not in the shot, the other is holding the camera, and when they are both in the shot, no one was standing behind the camera, so they had to set it on a tripod or figure out a way to place it and set it in motion. With knowledge of how it was made, Seven Layer Dip becomes a testimony to considerable resourcefulness and apparent enthusiasm for the creative process of creating an action scene that is well thought out in terms of choreography.

Tenet (2020)

It’s a great feeling when you emerge from the cinema mystified by a film and you have a sense of returning from another reality or perhaps only back to the past, when the impression of having come into contact with something fascinating and absorbing was fresh and relatively frequent. Nolan is the last great fantasist of our age, a director who can still get inside our heads with his spectacular roller coaster. His films are truly creations meant to be seen in the cinema, not only with mammoth sound design and opulent visuals, but also with enchantment of the viewers, who have to give up the control over the film that is given to them by the remote and let themselves be carried away by the pre-set time that the director-protagonist carefully constructed. It is possible that the illusion will dissipate upon repeated viewing or absorption of all of the explanatory analyses and video essays. But it is perfect right now and, just like the characters in the film, I want to enjoy the blissful ignorance, to again be a teenage fan emerging enchanted from the cinema or at least to gaze enviously across the flow of time at the naïve youths from the perspective of a hardened veteran and wish them this genuine feeling of enthusiasm.