Reviews (536)

Mr. Teas and His Playthings (1959)

In 1960, Walt Whitman Rostow, later an advisor to President Johnson, published his famous book “The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto,” in which he outlined the teleological development of the capitalist world. The end/climax of history thus falls on the "age of high mass consumption." Consumer society ultimately triumphed/triumphs everywhere in the world. What could be written (pseudo)academically, Meyer managed to capture perfectly in a cinematographic way. That is because he filmed at the end of the prudish puritanical American era, and his protagonist at least formally tries to rid himself of his pleasure in women/sex, and even in the title of the film he is presented to us as immoral. Yet Meyer knew well that a person in the culmination of Western history would not deny themselves their pleasure in the future, let alone feel immoral. As prophetically stated, some people want to remain sick. Mr. Teas is the spiritual father of all "Californication," etc., that is, those of mass culture who turn their mundane appetites and limiting their own responsibility in favor of adolescent and comfortable mundanity into the prototype of the easygoing/cool person. This comment is not a lament of an old-fashioned moralist, but a lament over how after so many other vital and natural human qualities, sex has become just another commodity in the wheel of mass culture. The fact is that B-movie director Meyer unwittingly captured it better than any sociologist or historian.

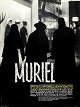

Muriel, or The Time of Return (1963)

Resnais was not an auteur - his films relied on the quality of his collaborator, the scriptwriter. For this reason, Muriel, or The Time of Return showcases the director's progressive paralysis: Hiroshima mon amour by Duras, Last Year at Marienbad by Robbe-Grillet, with the third feature film Muriel relying on the script and dialogues by Jean Cayrol, who, although a talented writer, simply did not reach the same level as the previous names. The theme of the intertwining of time and its relationship to the subjectivity of the characters (similar to all the mentioned authors as well as Resnais himself) is present here... actually, just like everything that was already included in the previous two films. This is where Resnais' paralysis manifests itself - he reached his peak in his first two works, and everything afterward is merely a hesitant imitation of himself (but only partly himself, as it is apparent that Resnais tried to mimic the spirit of Duras/Grillet in his early films, although he simply did not possess it), or empty copies of the corresponding formal procedures (flashbacks/flash-forwards, etc.) as in Stavisky. /// However, it would be unfair to assess Muriel solely based on the internal criteria of the director's career - it is still and will always be a work of narration and formal techniques safely surpassing the vast majority of other films. In the brilliant editing sequences, the time sequence is not followed, but rather time-space crystals are created, whose surfaces reflect different temporal sediments in various directions, bringing the past closer to the present, space, and characters according to their internal relationships, and, last but not least, anticipating events caused previously in another plane, which will only be revealed later.

Murmur of the Heart (1971)

Malle captured the atmosphere of adolescence and pubertal/hormonal confusion realistically and intuitively, which is definitely not easy and deserves recognition. Unfortunately, throughout the two-hour film, he hints at a variety of topics (especially the Oedipal relationship with the mother, the influence of the army and paramilitary environment - scouts - on adolescence during the French decolonization wars, strange relationships within the family...), which would be worth further exploration. However, the viewer does not get to see that, and Malle appears to me as a rather poor film psychologist. He “only” achieves a very skillful portrayal of adolescent adventures, complemented by a retro 50s feeling. The final scene with the whole family thus reaffirmed to me, in the context of the entire film, that I shouldn't look for any irony or ambiguity in it, but rather only a guide to understanding the film as a whole: understanding humor with insight towards the actions of the main character.

My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1984)

This film is definitely not about uncovering the obvious or hidden faces of Stalinism, but rather about gaining insight into the life of police investigator Lapshin and his friend - and yes, insight into the 1930s, but I would rather not draw complex judgments about this time period from this film. It's not so much about the time period but about a person. A person searching for happiness and security in the face of a harsh and insensitive world that he knows from his everyday work and his past life (and here, the "time period" plays a role). A person whom we are waiting to see if friendship and love will finally help him emerge from loneliness. Despite the mostly black-and-white camera and the omnipresent Russian winter and gloom that engulfs the viewer (and despite the somewhat disorganized first half), the film creates a nostalgic, sensitive, and perceptive atmosphere, best illustrated by the opening scene of the people getting to know each other when the camera familiarly examines and passes through a series of details in the narrator's story (the son of Lapshin's friend) while leaving the "big" outside world behind his windows.

My Way Home (1965)

A young middle school student wanders through a country where the war just ended, but the army has not yet left. You could say that the young man's youthfulness prevents him from saying goodbye to the war, as if he is moving between the desire to get home to safety and on the other hand, participating in the enterprise of real men (like when he puts on an abandoned uniform - is it because he is cold, or does he want to wear the uniform, to be seen as a soldier, even if he will surely be captured?). Later, the occupying army does indeed capture him. He behaves like a true soldier and a Hungarian. He tries to escape from the Russians, or rather from a Russian. But then the screenwriters and the director show an example of universal reconciliation. The law dictating the young man's behavior changes. He no longer acts like a Hungarian, like a soldier (which are categories dividing, generalizing, and heteronomous people), but like a Human. Indeed, a true human helps others regardless of nationality or uniform. Cinematographer Tamás Somló once again showed himself in full glory.

Nanami: The Inferno of First Love (1968)

The inferno turned upside down. It ultimately rages outside the boundaries of her first love's inner being and accuses her surroundings - her era. This is because in the context of the director's work (and the film itself), it is evident that the documentary retrospective of the personal history of the characters serves not only as a mere dramatic construction of characters outside of space and time, but on the contrary, it attaches them to their social conditions: the increasingly frequent structures of perversion on the part of adult male characters, the disintegration of the traditional family, and women's emancipation form faithful backdrops for the psychology of the main characters, which also adorn the habitat of every modern film viewer. Moreover, what was common in this (and the best) period of world cinema - the story, psychology, and general statements - are combined with formal equilibristics, whose visual style may be self-serving in some places, but not unimpressive. In any case, the film deliberately does not achieve the status of a truly experimental film. The first love of the (post)modern era will have to overcome internal and external obstacles (forever?), but will never again encounter innocence, violated already in childhood and violated by perversion, and passed from victim to victim like from generation to generation.

Nathalie Granger (1972)

The slow pace of minimal action is filled with apathetic characters constantly waiting for an unpleasant resolution in a house that should be a model of a warm family idyll were it not for the behavior of one of the children. At first glance, Nathalie’s angel, even without her physical presence in most of the film's plot, "floats" in it like a black moth coming from the future and paralyzing the present. The indifference of the characters is only broken by the arrival of a strange wanderer. The film may not want to convey any message, and perhaps we are just meant to immerse ourselves in the atmosphere of the house and its inhabitants. However, it is also possible to interpret a message about the growth of indifference and violence in an increasingly automated and alienated society (e.g., the washing machine, the educational system), as presented in the form of a radio broadcast of a pursuit of two teenage murderers, whose counterparts roam the screen in a slightly younger representation. It is thought-provoking in this regard that the male characters in the film are more emotional and action-oriented (Depardieu, the teenage murderers) than all the female characters, who, however, as mentioned above, will also "mature" to this stage. This is perhaps Duras' unintended contribution to the ongoing process of women's emancipation in society... The formal playfulness (repetition of the scene of the school interview, allusions to diegetic and non-diegetic music, and the camera and mirror games) is enjoyable, but after appearing sporadically, it is no longer further developed.

Navire Night (1979)

Love slides along the telephone line like a gaze through deserted shots. Where we expect to find a person, we find emptiness, and where we come across a face, we find someone else, someone different from who we were looking for, than who we always looked for, but never wanted to see: because she, whom sight would not recognize and would only truly know with eyes closed in the darkness of the world, cannot be seen, but especially not by me - there is no image in the text of desire, there is nothing to see here. The Boat called Night faces the Night of Time. Blind. Only with a blind gaze, wandering over her black image, can one see the one who needs to be hidden behind words, voices, Paris, so that they can merge with her, the one who cries in the night, dissolved in general desire, distorted by a chasm; the one transformed beyond recognition, beyond their own recognition… It is because only the one who allows themselves to be lost in the general desire of the night, where love knows no names, only faces that can belong to anyone at any moment, will not be afraid to tear away the scratch from their self and their you and look behind the black image, enter it, from which everything came and into which everything will submerge. The whole night...

Necropolis (1970)

The average viewer looking for a horror film will indeed find it, but in a reversed form, because this film is not the domain of conventional cinema, but quite the opposite - the average viewer will run away from the film in horror (by which Necropolis paradoxically fulfills one of the ideal goals of the horror genre). It is, in fact, a total European art film - the end of the 1960s, counterculture, long intellectual declamations in even longer shots, and traditional B-movie and historical characters turned upside down into pop-art material used to create completely different meanings (Frankenstein as a thinker/propagator of revolutionary ideas in the style of consciousness-raising, Bathory as a modern neurotic woman dissatisfied with her husband, etc.). The entire film is shot in a studio using minimalist but aesthetically exquisitely crafted sets, which provide a great background for detailed studies of characters and actors with the slow and static camera. The actors are chosen in an interesting way because they mirror the multi-layered nature of the film - from more avant-garde and art actors like Clémenti or Viva to the supremely avant-garde playwright and director Carmelo Bene, and even Bruno Corazzari, who acted in spaghetti westerns. The film also has a decent humorous component and, moreover, even at first glance, the sequence of scenes, which is only loosely connected, has a certain internal logic and relationships.

New Old ou les chroniques du temps présent (1979)

The subtitle "Chronicles of the Present Time" illuminates two aspects - 1) a countercultural perspective on the history of the present, viewed logically in an experimental but also popular culture (Clémenti met Warhol during the filming process) manner; and 2) the position from which this perspective was formed, i.e., the lived-in and intellectual world of the "chronicler," /// "The period from the making of Belle de Jour was wonderfully productive, but in 1971 Clémenti was imprisoned in Italy on drugs charges. He never seemed to fully recover from the ordeal, but the experience led to a book and a film, New-Old (1978), which he described as "my diary of my life before and after 1973." (The Guardian, B. Baxter, 21.1. 2000). New Old is less condensed than Clémenti's previous two films (which is understandable given its significantly longer length), yet it still successfully builds on their previous methods (especially the multiple psychedelic exposure in the passages of the impressions of the time), enriched here by capturing one's own thoughts or ideas of friends and fragments of the life of one's own circle of artists and friends. The film differs from the otherwise formally similar films of Clémenti's friend Etienne O'Leary, who also subjectively captured the surrounding world and his own privacy, but could not coordinate the viewer's perception, so his films appeared as a random mess, even though they captured the same things as Clémenti, who, however, is able to better distinguish both levels and make them more comprehensible and impressive.