Reviews (536)

Salt for Svanetia (1930)

Another expressively non-documentary film capturing the modernization/sovietisation of underdeveloped areas of the USSR, which were numerous not only on the periphery of the country - a similar film is Turksib (1929) about the introduction of railways to Central Asia, but generally also the "invasion" of tractors into Russian and Ukrainian villages in Old and New and Earth. In this specifically Soviet construction genre, documentary (that is, an ethnographic excursion into the living conditions and traditions of the locals) mixes with fiction - specific stories of people, which, from the perspective of the authors, reveal the essence of their communities. For example, the fate of the woman abandoned by society is not so much a part of a narrated story, but rather a timeless metaphor, a contrast to the everyday life and traditions of a Georgian village (hopefully no viewer thinks that the contrast between a starving mother and child and wasteful religious festivities happens at the same time). It is therefore parallel montage, not cross-cutting, that we are watching! That is exactly and mainly true for the final construction shots - we can only be dismayed by the discrepancy between the film and reality if we do not understand the film and its message as parallel montage (a promise, possibility, future of Georgia contained in October and its builders), but as simple cross-cutting.

Sud dolzhen prodolzhatsya (1930)

A feminist educational film, which shows the greatness and tragedy of Soviet cinema at that time. Without a doubt, there is nothing to criticize here in terms of the content of the deserving and progressive theme of the struggle of a wife-employee from the electrical plant for recognition of her right to work (by this I mean emancipation from the "natural" sphere of "women's" self-realization). The question of women's emancipation was raised in the USSR in the 1920s - thanks also to that abominable "totalitarian" always criminal ideology that ruled there at that time... - as a problem for an accelerated/"revolutionary" solution. We can also state that, compared to the West, there were often more discussions about such "feminist" issues in public discourse. So, wherein lies the tragedy? In the fact that the main protagonist’s struggle, during which she exposes both her husband and high-ranking people as advocates of surviving bourgeois sexist views, will soon become the norm for Stalinist purges and denunciations – yet now, they are of a political nature. /// The fact that Dzigan managed the formal aspects of the matter very well - his sense of composition of large units, also filmed in the studio, or dynamic editing (which, although not reaching the sophistication of the classics of the montage school, is nevertheless aesthetically impressive) - is also worth noting.

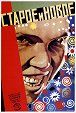

The General Line (1929)

To be able to capture things beautifully, originally, and suggestively is an art, but discovering new, previously unsuspected, or unnoticed relationships among things is mastery. Eisenstein was able not only to capture the motionless beauty of things, nature, and masculine faces (otherwise terrifying...), but he was also able to capture the relationships between them. It is in the relationship between two or more things that tension and movement arise, which he was able to not only breathe life into but also capture with his dexterity. That is why there are both beautiful details and the dynamism of scenes in such situations, which would bore a different filmmaker capturing the construction of an agricultural cooperative in two silent hours. The analogy with humor and seriousness, the ability to create a visually breathtaking experience from the most ordinary scenes of haymaking or the operation of a milk centrifuge, is simply mastery, in my opinion. There is no choice but to agree with another master of the silent era, Griffith: "What the modern movie lacks is beauty – the beauty of moving wind in the trees, the little movement in a beautiful blowing on the blossoms in the trees. That they have forgotten entirely. In my arrogant belief, we have lost beauty." Considering the historical context of the film in the context of Russian history and the betrayal of the author's commitment to Stalinism, it is a tragic beauty.

Turksib (1929)

This highly visually captivating documentary by Viktor Turin had a great influence on filmmakers in the West, especially on British and Anglo-Saxon documentary production. Richard Leacock saw the film at the age of 11 (1932) and it shocked him so much that he internally decided to express himself through the camera. I have heard that it also had a considerable influence on the work of John Grierson. After the initial more drawn-out "ethnographic" and geographical delimitation of the issue, the viewer is fully drawn into the struggle between man and extreme nature. Or as they say, "nature is tenacious, but who is more tenacious? - Man!"

The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (1927)

It is only characteristic that one of the members of the large family of documentary films was created for a purpose that does not align with the task that prevailing common sense imposed on it yesterday and today - to neutrally reflect reality and objectively retell history. The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty, the father of the montage documentary, inherited a clear socio-political motivation from its dual mother, Esfir Shub,and the October Revolution. The description of facts overlaps with a particular interpretation that denies universal objectivity and - let us add to it with folk wisdom - "criminally distorts reality." If this naïve opinion, which stubbornly denies that every interpretation is a crime committed against "reality," but with the caveat that interpretation can never be avoided and is a necessary addition to every event, every text, and in this case, archival material can be easily refuted, it is possible by pointing to this film. Since the montage documentary, which, with its structure, was most suitable for a documentary film about more recent history in general and has therefore become its most common prototype to this day (with minor modifications: intertitles replaced by voice-overs and supplemented with talking heads), it found its first portrait in a film with a clear ideological function. It is up to each modern viewer to understand that the ideological content of the documentary (ideological in the sense of worldview, ideas, etc.) can change, but that the ideological-interpretive function is and will remain irreducible. After all, in the indifferent face of Nicholas II Romanov, there will always only be what we or the time period want to see in it and what the montage composition, connecting it once with "bloodiness" and another time with "holiness," will embed into it.

The Overcoat (1926)

G. Kozincev was able to create very high-quality films throughout his career, and it must be noted that he was able to do so in various styles within the history of European cinema. In The Overcoat, we witness Kozincev's/Trauberg's unique incorporation of elements of German expressionism: indeed, the winter St. Petersburg under the cover of night, in which long shadows of criminals and bureaucrats crawl in the light of gas lamps, reminiscent of a certain Murnau vampire, is similar to the supernatural world of the German classics; the mysterious "surrealistic" story (after all, it is Gogol about Russian bureaucracy ...) about the world of bureaucracy, which is even further removed from the ordinary person than the most magical world of the relevant German classics. It is astonishing that as early as 1929, the same directing created The New Babylon, which is characterized by a high-quality (although not at the level of the best) reception of the montage school elements of their compatriots, in which, unlike in The Overcoat, the notable stylization, the tight little fictional world, and the game with the camera will give way to the game with editing and large, directorially demanding scenes with political and historical motivation. It is unnecessary to mention that Kozincev would end his career as a master of the most faithful and realistic film adaptations of classical Shakespearean dramas.