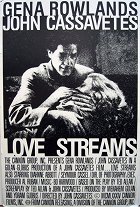

Directed by:

John CassavetesCinematography:

Al RubanComposer:

Bo HarwoodCast:

Gena Rowlands, John Cassavetes, Diahnne Abbott, Seymour Cassel, Leslie Hope, Xan Cassavetes, Gregg Berger, Raphael De Niro, Al Ruban, David Rowlands (more)Plots(1)

With Israeli filmmakers Golan and Globus watching over him, director John Cassavetes was guilty of less self-indulgence than usual, and the result is one of his best movies ever. Appearing for the first time in a movie that he also directed, Cassavetes and real-life spouse Gena Rowlands team up as a brother and sister, Robert Harmon and Sarah Lawson. The screen exudes their intensity; and despite their apparently different personalities, a oneness of spirit unites them. Robert is a well-known author, who is researching a book on prostitution and becomes the den father to some lively ladies of the evening. His research takes him on nightly forays to the underbelly of town. Sarah is a delicate creature in the throes of a divorce and custody battle against her husband, Jack (Seymour Cassel). The intercutting of the two stories contrasts the tawdriness of Roberts life to the exemplariness of Sarahs. For half the movie we see their separate lives and wonder when and if they will get together. Rowlands is wonderfully convincing in her many opportunities to play unusual scenes. Cassavetes also has his moments. More an amalgam of telling bits and pieces than a real story, owever, it all seems to work. (official distributor synopsis)

(more)Videos (1)

Reviews (1)

Truly a very "personal" Cassavetes film and also in its own way somewhat optimistic. I would perhaps use the word sentimental, although not in the usual pejorative sense. Cassavetes already knew back then that he didn't have too many years left, and without being a fan of incorporating the author's personal life into the final work, it shows in the film with his not-always-well-combined split between scenes of pessimistic despair and optimistic refusal to give up on life without love. On one hand, it’s classic Cassavetes - solitude, awkwardness, boredom, and alcohol, which gets to your head (in the film, Cassavetes occasionally reminds us of Gazzara from The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, while Gena Rowlands also reminds us of A Woman Under the Influence). On the other hand, the grotesque scenes are deliberately comedic (Rowlands and her suitcases). In between lies a middle ground of comedy, which is chilling - again, classic Cassavetes - in which the characters desperately try to convince themselves that happiness is possible. The question is: why are these relaxed scenes in the film? Probably precisely because the author somehow did not want to forget the "optimism" and hope in anticipation of the end, I think. That wouldn't be a problem if these scenes (in my opinion) didn't somewhat disrupt the tightness of the entire film and create an impression of authorial and script inconsistency, which can only be explained by pointing to something outside the film itself.

()