Reviews (838)

Christmas with Elizabeth (1968)

My Sweet Little Village without Menzel’s refined touch. Both when he is at home in his dingy studio apartment and when he is at work, the solitary truck driver played by Vlado Müller sticks to his routines, which long sections of the plot are dedicated to depicting. In her only film role, Pavla Kárníková portrays his unpunctual assistant, who conversely has no respect for order or authority. They can’t stand each other at first. They’re sure about that in advance. He sees her as a “whore” and a “bitch”, while for her, he is a grumpy “old man”. Through their dark past, however, they gradually find common ground and come to realise that it is possible to step out of the roles to which they have become accustomed or that society has assigned to them. In his case, it is the role of a curmudgeonly bachelor who holds others at arm’s length, whereas her role is that of a troubled “slut”. Unable to express their feelings in a healthy way, the two outsiders come together during Advent, and the undecorated tree and lonely Christmas dinner add a sense of melancholy to the raw, authentically gritty story. In the context of the collaborative works of Kachyňa and Procházka, Christmas with Elizabeth fits in with Hope, which took a similarly humane approach to depicting the relationship between a prostitute and an alcoholic, other social outcasts who in the 1950s were condemned to the roles of criminals unworthy of any understanding. 75%

The Zone of Interest (2023)

Though throughout most of the film we don’t see anything other than an outwardly ordinary German family, the layered soundtrack, which mixes the chirping of birds and the murmur of a river with a constant mechanical drone, evokes an almost indefinable feeling from the first minutes, a feeling that something intimately familiar seems strange and oppressive. The resulting effect is best described by the term “unheimlich” from Freud’s psychoanalysis, i.e. uncanny. Zone of Interest is extremely disturbing in its ability to capture the abnormality of the everyday. ___ The unchanging, rigid apathy of the depicted world is underscored by predominantly static shots without artificial lighting and with great depth of field. The cameras are positioned in different corners of the house and garden like in a reality TV show. They record the movements of the actors without artistic stylisation, thus evoking an impression of the distant past. Not even the editing adheres to the principles of standard narrative cinema. The switching between cameras depends on which room a character has just entered. Everything thus seemingly takes place in the present tense. Subjectivity and creativity, or rather the possibility of averting one’s gaze and disrupting the order of things, are suppressed. The tasks that Höss carries out are mindless administrative work. Genocide is a logistical process. ___ If we wanted to locate the source of the tension that pervades the whole film, it would be the clash between what the Hösses are willing to see and what happens outside of their house and garden. Glazer’s distinct style is a form of rejection. He consistently avoids aestheticizing one of the greatest tragedies of modern history. At the same time, he succeeds in using empty space in a way that is far more powerful than direct depiction. Because we cannot see the other side, we are aware of what is happening there. Our effort to fill this gap leads to the fact that we cannot stop thinking about the ongoing violence. ___ Glazer also included night scenes shot with a special thermal camera. This involves a reconstruction of the story of a ninety-year-old Polish woman named Alexandra, whom Glazer met during his research. She became for him a symbol of resistance, a light in the darkness. Taking into account the perspective of those who actively resisted Nazism is one of the few elements that Zone of Interest shares with more conventional dramas about the Holocaust. Where other Oscar-winning dramas offer catharsis and a reassurance that humanity will ultimately prevail, Zone of Interest offers only a disturbing presentiment of things to come. We see that the concentration camp has become a museum where cleaners mechanically vacuum the dust and polish the display cases. A single glance inside the death factory peculiarly does not reveal any atrocities. Rather, it is characterised by the same emotionless routine that we saw in the Hösses’ bourgeois household. We have become accustomed to the presence of the Holocaust in our collective memory and in the media space. Zone of Interest shines a light on the mundanity, banality and elusiveness of the evil to which we contribute merely by remaining indifferent. 90%

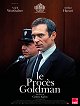

The Goldman Case (2023)

The Goldman Case is a masterclass in how to grippingly direct (and edit!) a courtroom drama that takes place almost entirely in a single room without needless embellishments (and, furthermore, is shot in the television format that corresponds to the time when the trial was held). In terms of acting and the screenplay, The Goldman Case is equal to Anatomy of a Fall, at whose centre stands a similarly complicated character and which raises similar questions (Doesn’t the one who can tell the more convincing story and give a better performance win in court? Do words have more weight than actions in the end?). And though it involves a case from the 1970s (a left-wing Jewish activist denies murder charges), in the second plane the film delivers an almost sociological overview of French society at the time, the clash between the right and the left that plays out in the courtroom, the inability to see a person outside of the box in which we have placed them based on their political orientation or background, and the unwillingness to see that some facts can be black and white at the same time, all of which is in some ways reminiscent of today’s culture wars. 85%

Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One (2023)

More graphically than the previous instalments of the M:I franchise, Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One raises concerns associated with the future of humanity and of Hollywood. The film, whose main villain is an extraordinarily powerful artificial intelligence, was released to cinemas during the dual strike of Hollywood actors and writers, who in addition to fair compensation also demanded a guarantee that they would not be replaced by modern technologies. The computer-generated illusions in the film threaten the approach to truth and relativise the ethical categories of good and evil. Ethan Hunt/Tom Cruise is naturally the only safeguard against machines taking over the world, the last link holding human society together (this is literally true in the final action scene, when his partner uses him as a ladder). What awaits him is a confrontation with the most powerful adversary he has faced yet, which collects our best-hidden secrets, reshapes reality and is everywhere and nowhere. In other words, he will have to take on a (false) god, whose interests are represented by a villain with the biblical name of Gabriel, and the key to controlling it is in the shape of a cross. ___ Though few people in Hollywood today are able to so effectively evoke the dizzying feeling of forward motion as a running Tom Cruise, Dead Reckoning is to a significant extent a film of reversions, to the old faces and analogue technology of the Cold War period, to the protagonist’s past and to the skewed angles of De Palma’s paranoid first Mission: Impossible. And even deeper into the past. To The General, Hitchcock’s comedy spy thrillers and related 1970s caper comedies like What’s Up, Doc? McQuarrie combines the structural principles of the cinema of attractions and classic Hollywood, but he intensifies the situations and takes them to such an extreme that even the characters sometimes laugh resignedly over their impossibility. Tension arises between the (unseen) classic and (self-reflexive) post-modern approach to style and narrative when the film alternately fulfils and defies our expectations, as it is playfully ironic at times and tragically romantic at other time. Similarly to the way Hunt defies the algorithm and how the protagonists are aided by disguises and advanced surveillance technologies, which fail repeatedly, however. In the end, they can rely only on human bodies, ingenuity and teamwork. ___ The characters’ distrust and suspicion toward what they see and hear is expressed in the dialogue scenes by the tilted camera shooting from up close and in decentred compositions of the actors’ faces. Sometimes without establishing shots, which, together with the hasty editing (including cross-axis jumps), intensifies the feeling of disorientation and the impossibility of determining what is true and who is running the show. At other times, usually while the next course of action is being planned, the camera uneasily circles the characters. Thanks to this, even the chatty explanatory sequences are thrilling and there are practically no statics moment in the film. The almost cubist composition of the picture occurs roughly at the midpoint of the narrative during the meeting of most of the key players at a party at Doge’s Palace in Venice. The characters’ dialogue as they try to figure out their adversaries’ motivations is edited in the rhythm of the diegetic background music. Their verbal shootout is reminiscent of a dance performance, as every camera movement is synchronized with the soundtrack. Also in other scenes, though not as conspicuously, the information conveyed is of comparable importance as the aesthetic pleasure of the interplay of shapes and lines. For example, during the chase through the narrow and dark streets and canals of Venice, the order of shots is not determined only by the continuity of the ongoing action, but also by the rhythmic alternation of contrasting and complementary angles and movements. ___ The episodically structured film traditionally comprises several massive action sequences, each of which having its own objective, obstacles and course of development. At the same time, they are firmly interlinked. Each one prepares us for what will happen next (which doesn’t always go according to the presented plan) and sets in motion another notional cog in the flawlessly tuned mechanism. The chosen locations also complement each other, as they give the characters less and less room to manoeuvre (from an expansive multi-level airport to a closed train). Almost every sequence works with a tight deadline and the necessity of precise timing, both across the given sequence and in its constituent parts (for example, the necessity of escaping from the car before it gets destroyed by an oncoming metro train at the end of the Rome sequence). ___ Unlike in blockbuster comic book adaptations and the high-octane, progressively dumber Fast & Furious movies, the human element is never overshadowed by the shootouts and explosions in Dead Reckoning. On the contrary, they are doubly suspenseful thanks to the chemistry between the believable characters. Their characterisation, which is carried out without pauses in the action or during their preparations for the next task, is skilfully connected with certain recurring motifs and props (e.g. Hunt’s lighter, the passing around of which among the characters reflects the development of the relationship between Grace and the protagonist). That’s what the franchise is about, as Cruise doesn’t hesitate to risk his own life again and again with maniacal determination in order to convince us that an intelligent machine can never do anything as spectacular as a human (or a team of humans) can do. In the latest instalment of the M:I franchise, which is the most narratively harmonious and stylistically experimental of the lot, he does this for the first time not only in the subtext, but in the foreground. The time for subtlety has passed. 95%

Ferrari (2023)

Enzo Ferrari teaches his son that when things work well, they are pleasing to the eye. Michael Mann follows the same maxim. Ferrari, another of his portraits of an obstinate professional in an existential crisis, is a joy to watch thanks to its narrative cohesiveness and the fact that it rhythmically fires on all cylinders. During practically every shot in the exposition, we learn some important information that will be put to good use later in the film. At the same time, the exposition introduces the governing stylistic technique consisting in the use of duality and contrasts (e.g. light scenes with Enzo’s mistress vs. dark scenes with his wife). Slower scenes regularly alternate with faster ones, movement alternates with motionlessness and the melodramatic (and utterly operatic in one scene) exaggeration of certain emotions, particularly sorrow, which both spouses deal with, each in their own way. Mann follows the example of classic Hollywood directors like Hawks and Sirk and lets the mise-en-scéne tell much more of the story than other contemporary directors would allow. At the same time, he defies the conventions of classic biographical dramas as he focuses only on a brief period of Ferrari’s life and, instead of creating artificial conflicts, he superbly dramatises everyday encounters and ordinary business operations (paying wages, signing documents, concluding agreements with investors). This feel for detail also contributes to the believability of the fictional world. Ferrari’s work always clashes – either constructively or destructively – with his personal life (Ferrari finds common ground with his son thanks to his work, but he also loses his wife because of it). The lion’s share of emotion and excitement is typically found in the cinematically brilliant scenes of races, which represent Ferrari’s greatest passion. Unlike other sports movies, however, such scenes do not bring catharsis, but rather recall the fragility of life (thanks in part to the excellent sound design, the race cars of the time really do not seem safe) and recognition of the fact that however hard you try to have everything under control, certain events cannot be foreseen and you ultimately have no choice but to accept them and somehow incorporate them into your life story. 90%

Wonka (2023)

Timothée Chalamet plays a start-up entrepreneur who is hindered in selling magical chocolates with giraffe milk and the tears of Russian clowns by Hugh Grant in the role of an orange Oompa-Loompa and a chocolate cartel whose members meet in a hideout like villains from a Bond movie (it’s located under a church with chocoholic monks and can be reached only via an elevator in the confessional). Though Wonka has a generic, pseudo-Dickensian plot with by-the-numbers twists, strange jumps between scenes, a sticky-sweet sentimental ending and one-dimensional characters whose actions are not convincingly motivated, it is – in terms of its visuals and language (in both the dialogue and songs) – a captivatingly imaginative fairy-tale musical in the mould of Mary Poppins. It’s a shame that – in spite of a number of unhinged moments along the lines of The Mighty Boosh (and other British series represented here by their actors) – it is closer to the glossiness of classic Hollywood than it is to Dahl, whose children’s stories were not just extremely weird, but also very dark, which Wonka, as portrayed by the bland Chalamet, is practically not at all (unlike earlier adaptations by Mel Stuart and Tim Burton, which were based on finding a balance between light and shade). He doesn’t address the bigger internal conflict – teamwork, which he seemingly should have gradually grown into and which hasn’t been a problem for him since the beginning (he also involves all of his friends in the running of the shop). Wonka is rather a sweet treat made with ingredients of varying quality than a rich taste experience that will carry you away. (By the way, I have no problem acknowledging that, for example, the first Rambo is a Christmas movie because it takes place during the holidays, but in the case of Wonka, I can find no reason to classify it as such – is it enough for the movie to be released in December and for its characters to eat a lot of chocolate?) 75%

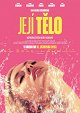

Her Body (2023)

Adam: Why are you hopping? Andrea: Why are you walking? This bit of dialogue essentially contains everything that we learn about Andrea Absolonová’s motivations over the course of (not quite) two hours. Her Body is thus an apt title. The film makes no effort to psychologise her (and it is more consistent in this respect than the recent Brothers). We see from up close what her body has been through in various phases of her life, but we do not get a look inside her head. The scene involving an interview with a journalist indicates that she just didn’t have much to say. In the context of biographical dramas that have the need to explain why someone did this and that, it is an original approach. But to what end? The inability to go in depth isn’t offset by the originality or intensity of the stylistic techniques. It is neither carnal nor hard enough for a body horror movie. The only unpleasant scene is the one in which Andrea is on her hands and knees after being injured and stretches her bruised body. Otherwise, the film is remarkably easy to watch. Even when the protagonist is lying in the hospital with a neck brace or with a brain tumour, she looks great (several times I recalled what Ebert said about “Ali MacGraw’s Disease”: a movie illness in which the only symptom is that the patient grows more beautiful until finally dying). In fact, the family scenes with her father and mother are painful, though only because of their theatrical stiffness and unbelievability, when I had the feeling that I was watching several strangers (who conspicuously do not age with the passage of time) pretending to be blood relatives. We learn very little about the workings of the porn industry at the turn of the millennium. The story is cut down to basic events. There is no context (the motif of working with one’s body as a tool could have been made more multi-dimensional by emphasising the obsession with performance and success that became normalised in the 1990s). Andrea simply just has sex with various porn actors. She doesn’t deal with anything else around her. She doesn’t have to. Everyone is extremely kind and understanding. It’s nice that the film doesn’t take a moralistic stance toward porn (unlike, for example, the Swedish film Pleasure, which didn’t take a stance toward anything due to its cautious approach to the lives of actual people). It’s simply another physical activity at which the ambitious protagonist wants to be the best…which is simplistically emphasised by Adam’s line “you’re not in a competition here” (and there are plenty of similarly superfluous, leading statements). But what else? The problem with the film is not that it doesn’t go to any great lengths to explain what we see, but that it simply has nothing to explain. It’s hollow, it’s neither entertaining nor moving, and it doesn’t create dramatic tension. It does not have a clear theme or point of view (a problem of dramaturgy). It merely reconstructs a few loosely connected episodes from Absolonová’s life without offering anything that would be surprising. She was an excellent diver, then she got injured, then she became a famous porn actress without making any visible effort and then died young. She had a close relationship only with her younger sister, but in a film teetering between docudrama and family melodrama, this motif is just as feeble and poorly developed as all of the others (e.g. the eating disorder). There is no added drama or emotion, no deeper reflection on anything. Just her (still attractive) body. 50%

The World According to My Dad (2023)

This film/discussion starter was obviously made in a primitive way, though with the tremendous passion and conviction with which it is necessary to undertake certain projects, however misguided they may outwardly appear to be. Simply because they can bring forth something good. For example, a climate that won’t kill us. The difficult effort to publicise Svoboda’s idea for a global carbon tax is intertwined with the buddy-movie story of a father and daughter (for whom the film is, among other things, a way to understand her dad). Thanks to this, the ending of the film is not entirely depressing, as it does a good job of showing how the protagonists’ relationship has been transformed during their mission together instead of highlighting failure. It also avoids being depressing thanks to the natural humour and the dynamic between the characters defined through, among other things, recurring situations (economical loading of the dishwasher) and endearingly goofy songs, which liven up the narrative whenever it seems that the wheels are about to come off. One of the few films about environmental sorrow that won’t leave you feeling dejected when it’s over. 75%

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

Martin Scorsese and Eric Roth have taken a muddled, mediocre book and turned it into a great American novel in film form. Killers of the Flower Moon is a monumental, multi-voiced and timeless chronicle of the fall of a community whose lust for wealth is stronger than love, even though its members are aware that they are preparing the next generation for the future through their own behaviour. The film is dark and slow and feels longer than The Irishman, for example, but that length is justified, as it makes it possible for us to gradually get into that community and see at first hand how greed and cynicism gradually and inevitably spread to the country, become entrenched and consume the characters. Throughout the film, we find ourselves in close proximity to a confident and seemingly all-powerful, yet essentially banal and sometimes comically obtuse evil whose proper punishment seems rather unlikely, which is exactly as frustrating and exhausting as Scorsese most likely intended it to be. By comparison, the voice of goodness is weakened by sickness and the “medicine” administered, and it is limited to naming the one who died (which is something of a Scorsese trademark). Despite that – and thanks to the dignity that Lily Gladstone radiates – it has a central, evidentiary role in the narrative. Killers is primarily an indictment of the murderers whose existence should ideally have been erased from American history (because many still profit from their crimes to this day) and an emphatic demand to give back a sense of humanity to those whose lives were reduced to a few thousand dollars decades ago; the director’s closing cameo leaves us in no doubt about this. ___ Scorsese directs his lament with the surehandedness of a master. This time, he economises on the spectacular dolly and Steadicam shots, instead relying on the actors and Thelma Schoonmaker’s feel for rhythm. As a message about the substance of American capitalism, his plunge into the darkness could eventually become an equally essential work as Giant (1956), Once Upon a Time in the West, The Godfather and There Will Be Blood. At the same time, the intense hopelessness and the atmosphere of irreversible decline reminded me of Tárr’s films. No, that won’t come easy in the cinemas for this proof that you can still make your magnum opus in your seventies. 90%

Tony, Shelly and the Magic Light (2023)

Czech (and Slovak) animation has again risen to the world-class level in recent years. This has most recently been confirmed by the Czech-Slovak-Hungarian stop-motion film Tony, Shelly and the Magic Light, which received an award at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival. Thanks to its amazing colours, lights (!) and original visual ideas, Filip Pošivač’s feature-length debut looks so good that I wanted to slowly pause every shot and savour it for a moment. In terms of its superb craftsmanship alone (for example, Denisa Buranová’s dynamic cinematography, which takes something from live-action filmmaking and contributes to the originality of the creative concept), this is an extraordinary film in which it never once seemed to me that the filmmakers made any compromises, let alone skimped on anything. And the story, written by Jana Šrámková, is also exceptional, not only in the domestic context, in the way that it is both comprehensible for children (judging from their reactions) and appealing to adults on a deeper level as it tells the story of the little big adventure of an eleven-year-old boy who glows. Since this film has quite a few thematic levels (depression, parenthood, self-realisation), you may find a different key to interpreting it, but for me the main thing was the unusually sensitive (and extremely relatable) narrative about the experience of a child who is neurodivergent (or simply different in some way) and – despite his loving, hyper-protective parents – tries to find his place in society, which is represented in the film by a single multi-storey apartment building. Based on the example of the titular duo, the film shows that it is quite beneficial to meet people or at least one person with whom you can identify (Tony is the only one who can see Shelly’s imaginings) and accept yourself in your own differentness to such a degree that you gain the courage to step outside of your own private (fantasy) world and to share with others your own inner light, which you had long seen as a limitation. Some have the good fortune to do that when they are eleven, some when they are twenty-nine. A beautiful film.